Sword Terminology

This article is sponsored by By the Sword.net where you can access excellent podcasts, events, historical sword-fighting classes and much more.

Much of the terminology used to describe historical swords is unique to the field. Fullers, ricassos, langets: these are names rarely found outside of blade-related circles—if at all. For beginners, this can be confusing and even veterans sometimes mix up their descriptions. Therefore, I thought it would be beneficial to those with an interest in the naming of parts if I wrote an introductory article on the subject and provided some simple diagrams. I say introductory because, with swords being in use for thousands of years across most global cultures, to list all of the names in use for every sword part would require more space than is possible here.

For this article, I will focus on the general terms we use to describe European-style swords in modern English. Much of this information is also applicable to describing ethnographic swords in English but if you’d like to learn more about other cultures’ swords directly, I have an article on Middle Eastern swords here, one on Indian swords here, and one on African swords here.

If this article proves useful to you please consider supporting me on Patreon, browsing merchandise or sharing it on your social media (which is free and really helps).

You can read more articles here or even buy an historical item of your own here. Thank you for visiting.

The Hilt

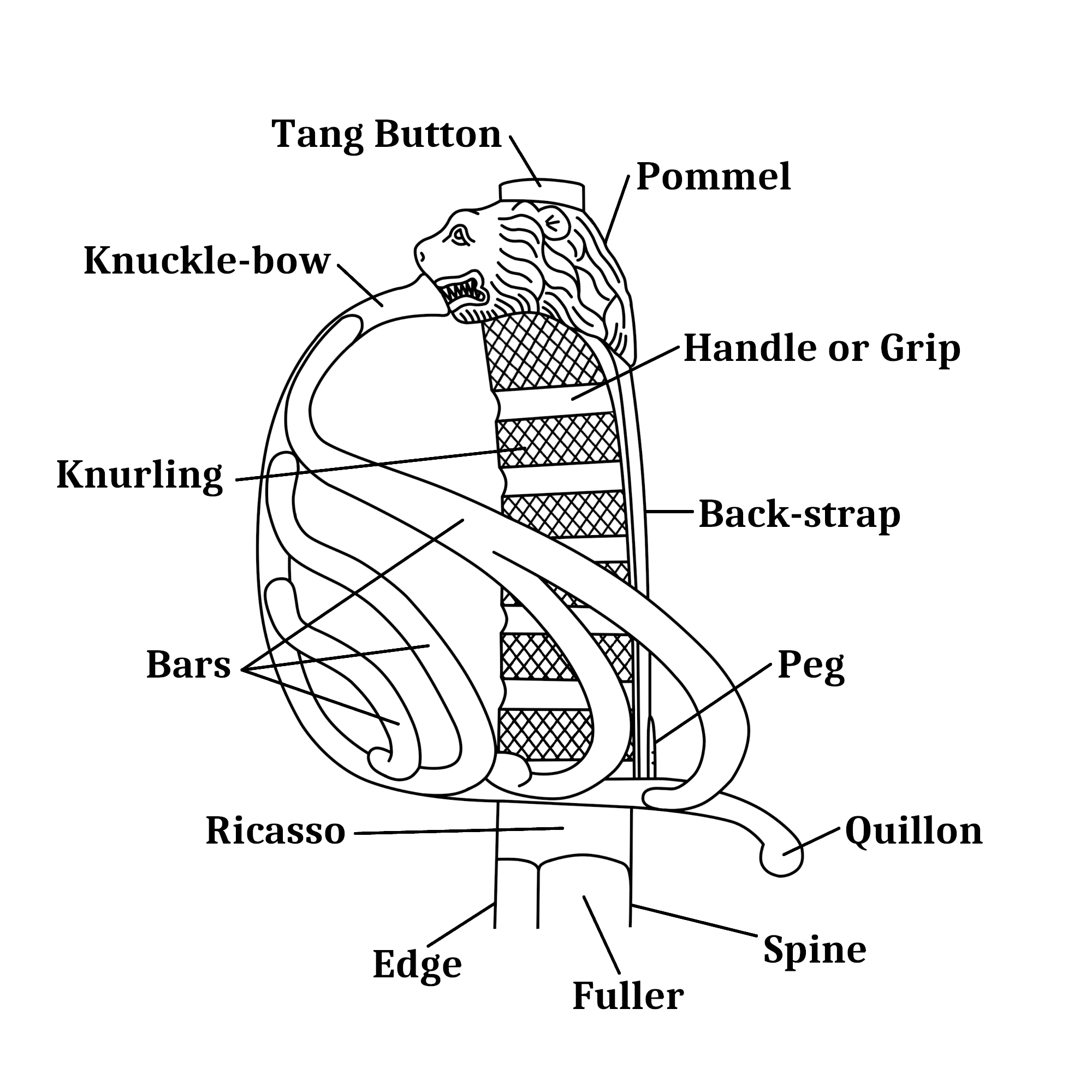

This usually consists of three major parts: a guard, a handle and a pommel.

The guard is perhaps the most variable of all sword components. Designs depended upon the way the weapon was used, the particular era’s fashions and the materials that were available to makers and so where one sword might have a simple cross-piece, another might have a highly elaborate basket. Even movable parts and firearms were incorporated into some of the more ‘niche’ guards. Naturally, many of these guards have their own set of terminologies according to their niche: pas d’anes were smaller bars that provided protection to the fingers of rapiarists and smallsworders, robust quillons projected laterally from medieval sword hilts and knuckle-bows arced from the fore to the aft for many sabreurs. Some guards included langets and these were metal bars of varying forms that projected along the blade and/or handle, their purpose being to help secure the hilt to the handle and to assist in the sword staying within its scabbard. While they are found in many European military swords they were especially popular in Mughal dynasty and Maratha dynasty South Asia.

Of course, some swords, such as the Russian shashka, eschewed guards entirely or had minimalist hand protection as found on the bebut, kindjal or gladius.

Handles were generally made from wooden ‘scales’ or tubes that covered the blade’s tang (the blunt section that entered the handle). The handle’s parts were kept in place by the tightness of the fit of the pommel, by a back-strap or by rivets and, sometimes, by ferrules. Some sword handles remained as naked wood while others were covered in cured marine skins, leathers, metal wires, metal sheaths, ivory—and all manner of precious materials. As with the pommel and the guard, the shape of a sword’s handle sometimes dictated how it was to be used in combat.

The pommel provided several benefits: it counter-balanced the weight of the blade, provided a hand-stop to the handle and informed the way the sword was used (see Indian tulwars, for instance). Pommels could be welded, screwed or peened onto the tang, sometimes with rivets passing laterally through the handle. Many pommels were decorated and some were even designed to provide the wearer with a comfortable place to rest the hand.

The Blade

The ricasso was a blunt section of blade nearest to the handle. In larger swords, a significantly-sized ricasso allowed for two-handed use but, generally, ricassos were short and helped the sword fit tightly into the scabbard. They also gave the sword maker a place to decorate or even to advertise, as can be found in abundance on Victorian military swords. The fuller was a groove set into a blade which made it lighter while retaining its strength. While some blades don’t have a fuller, others have several and in some cultures, their inclusion was seen as an aesthetic choice as well as one of metallurgical integrity. Beware of any source that calls the fuller a ‘blood groove’ and states that its inclusion was to prevent flesh from holding onto a sword through extreme suction. All of this has been so widely debunked that to imply it, particularly in print, suggests a lack of understanding.

In opposition to the fuller is the medial ridge. This is an elevation along a blade’s flat that stiffens the blade and makes it perform better in the thrust. The use of the point and whether it is better to thrust than to cut with a sword is still hotly debated. The main types of tip were the spear point, the hatchet point, the upswept point, the clipped point, the taper; though several more can be found—including such exotic endings as bifurcation.

Some Victorian blades had spines marked with a CP or an arrow and this denoted the sword’s ‘centre of percussion’, or in clearer terms, the best part of the blade with which to hit a fellow. The point of balance of a sword is another consideration as, the closer it is to the user’s hand, generally, the more nimble the sword proves. The part of the blade towards the hilt was called the forte (the strong) while the tip was the foible (the weak).

The Scabbard

Scabbards were usually made from metal, wood or leather: often, a combination of all three materials. As well as, in some cases, providing a canvas for decoration their main job was to protect a sword from the environment around it, especially during the rigours of a military campaign, and to stop a sharp blade from cutting its user’s leg or horse when mounted. If the scabbard was made from metal it usually had wooden inserts (or leaves) inside in to cushion the blade and prevent rattling when in transit and scraping during drawing and sheathing. Scabbards have an opening into which the blade slides and this is usually referred to as the throat. A throat-piece, or locket, was a metal collar that reinforced the scabbard’s opening. Sometimes, a scabbard can have both of these parts, usually as a locket that has a separate throat-piece.

Depending upon how the scabbard was carried, the locket might have a frog stud for vertical carriage or a suspension ring. In the case of the latter, there was usually a second ring placed a little further down the scabbard to facilitate more of a horizontal carriage.

At the terminus, there is almost always some form of a chape. This metal section was usually a short sleeve with a fin and it gave the tip of the scabbard some protection as it was dragged along the ground—a common occurrence. Chapes are sometimes called drags though the drag term is also used to denote just the fin used by some chapes. Occasionally, chapes can be made of wood and leather.

If this free article was useful then please consider supporting me on Patreon. By adding your support you gain access to a growing archive of useful articles, in-depth resources and advice, personal help with identifications and restorations, and, as I’m slowly liquidating my collection, early access to new sales. You can help out from as little as £1 (or $1) and everything helps. Thank you for your consideration.